The Section Boat: A Sumter Sportsman’s Legacy

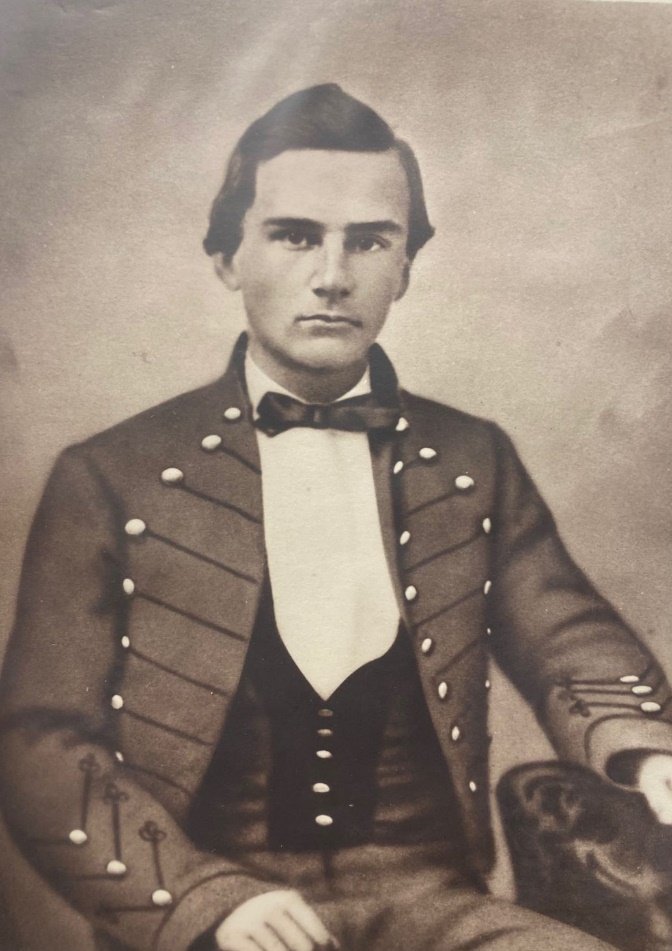

/In an era before outboard motors or trucks with trailers, hunting and fishing boats often became waterlogged and too heavy to move. Even if a sportsman could move his boat, bad roads to the river, and lack of space on a train or in a wagon made the transport of boats even more difficult. That is until the invention of the section boat by a Sumter man named Edward Richardson “Toot” Sanders. Mr. Sanders was born in 1845 in Sumter and was a Confederate Civil War veteran, master carpenter, and machinist. A shorter man, Toot always sported a bushy mustache and “several layers” of clothes no matter the weather, according to his family.

An avid sportsman Toot spent much of his time with his friends traveling in, and hunting around the Wateree River. After years of encountering all the typical problems of moving a boat to and from the river, around 1900 Toot used his skills as a master carpenter and machinist to create a unique solution. By constructing 3 small boats that could be nested inside of each other, then bolted back together to form one long boat, the section boat was born. This solved the logistics problems many hunters had previously dealt with.

Typically carved from cypress or longleaf heart pine, the section boat rapidly gained popularity all around South Carolina for its ease of use and transport. Some section boats reached up to 16 feet or more in length when bolted together, and many featured unique attachments or designs. The compact nature of the section boat also gave rise to a new breed of hunting dog, the Boykin Spaniel. The dogs small stature, hardy nature, and skills as a retriever made it an ideal hunting dog for the sportsmen who traveled the Wateree in section boats. The rise in the breeds popularity directly corelates to the invention and production of section boats in and around Sumter County. A humble man Toot never patented his design or profited off it, preferring instead to simply enjoy it with his friends. Toot Sanders passed away in 1922, and soon after as trucks to haul boats became more popular and affordable for hunters, the section boat gradually fell out of use. Today section boats are all but a myth on South Carolina waterways, with one of the very few known section boats residing at the Sumter County Museum, currently being restored for display.

Images include Toot himself, a section boat diagram (top), and one of Toot’s hunting parties in 1904. Information for this post was sourced from “The Last Section Boat: Raised From The Dead” by Mike Creel of The Resource, “Tales Of Toot” By Jacqueline Ulsh of The Sumter Daily Item, and Boykinspaniel.org.